|

Assemini, 11.11.2009

Egregi Lettori,

di seguito

riporto gli elementi che ho potuto raccogliere

sulle vostre monete (figg. 1 e 2)

Denario1, 43-42 a.C., zecca itinerante, Crawford

al n° 508/3 (pag. 518), Sydenham 1301 (pag.

203), indice di

rarità "(9)".

Descrizione

sommaria:

D. Testa di

Bruto2 a destra, barbato; attorno, in alto, in

senso orario BRVT

IMP3 attorno, in

basso a sinistra, in senso antiorario, L PLAET CEST4.

Bordo perlinato

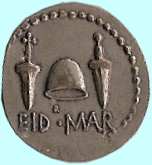

R. Pileo tra

due daghe; sotto EID

MAR. Bordo perlinato.

La ricerca

nel web di monete di tipologia simile ha prodotto i

seguenti risultati::

- http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/sear5/s1439.html

Sale: CNG 69, Lot: 1367. Closing Date: Jun 08,

2005. BRUTUS. Late Summer-Autumn 42 BC. AR

Denarius (3.51 gm, 12h). Mint moving with Brutus

in northern Greece. L. Plaetorius Cestianus,

magistrate. Bidding Closed Estimate $50000 BRUTUS.

Late Summer-Autumn 42 BC. AR Denarius (3.51 gm,

12h). Mint moving with Brutus in northern Greece.

L. Plaetorius Cestianus, magistrate. Bare head of

Brutus right / EID • MAR, pileus between two

daggers. Crawford 508/3; Cahn 22d (same dies); CRI

216; Sydenham 1301; RSC 15. EF, minor edge

crystallization. Rare and popular type. ($50,000)

Marcus Junius Brutus was the son of Marcus Junius

Brutus and Julius Caesar's former mistress,

Servilia. By 59 BC he acquired the alternative

name Quintus Caepio Brutus through adoption by his

uncle, Quintus Servilius Caepio. Brought up by

Porcius Cato, he was educated in philosophy and

oratory and long retained a fierce hatred of his

natural father’s murderer, Pompey. He began his

political career in 58 BC by accompanying Cato to

Cyprus. As triumvir monetalis in about 54 BC he

issued coins illustrating his strong republican

views with Libertas and portraits of his ancestors

L. Junius Brutus (who overthrew Tarquinius

Superbus, the last Etruscan king of Rome) and

Servilius Ahala (the later fifth century BC

tyrannicide) (Crawford 433/1 and 2, respectively).

In 53 BC Brutus served in Cilicia as quaestor to

Appius Claudius Pulcher, whose successor, Cicero,

found that ‘the honourable Brutus’ was extracting

48 per cent interest on a loan to the city of

Salamis in Cyprus, contrary to the lex Gabinia.

Brutus, the principled student, stoic, and

Platonist who wrote a number of philosophical

treatises and poems, seems an unlikely

tyrannicide, quite dissimilar to the vehement

Cassius. Despite his hatred of Pompey, he followed

him in the Civil War of 49 BC against Caesar, but

after the former’s defeat at Pharsalus he sought

and was granted Caesar’s pardon. He proceeded to

enjoy Caesar’s favor and was appointed governor of

Gaul in 46 BC, praetor in 44 BC and consul

designate for 41 BC. Perhaps under the influence

of his second wife Porcia, Cato’s daughter, Brutus

joined the conspiracy against Caesar, becoming the

leader alongside Cassius. The reaction of the

populace in the aftermath of the Ides of March

compelled Brutus to leave Rome in April 44 BC. The

Senate’s resolution to declare him a ‘public

enemy’ on 28 November 44 BC was soon repealed and

in February 43 BC he was appointed governor of

Crete, the Balkan provinces and later Asia.

Suspecting the intentions of Antony and Octavian,

Brutus went to Macedonia and won the loyalty of

its governor, Hortensius, and there levied an army

and seized much of the funds prepared by Caesar

for his Parthian expedition. Successful against

the Bessi in Thrace, he was hailed imperator by

his troops, but after the establishment of the

triumvirate in November 43 BC he was outlawed

again and joined forces with Cassius at Sardes. In

the summer of 42 BC they marched through Macedonia

and in October met Octavian on the Via Egnatia

just outside Philippi and won the first battle.

Cassius, as his conservative coins show, remained

true to the old republican cause, while Brutus

followed the self-advertising line of Antony in

the new age of unashamed political propaganda and

struck coins displaying his own portrait. Brutus’

estrangement from Cassius was effectively complete

when this remarkably assertive coin was struck

extolling the pileus or cap of liberty (symbol of

the Dioscuri, saviors of Rome, and traditionally

given to slaves who had received their freedom)

between the daggers that executed Caesar. In the

ironic twist of fate, Brutus committed suicide

during the second battle at Philippi on 23 October

42 BC, using the dagger with which he assassinated

Caesar. This extraordinary type is one of the few

specific coin issues mentioned by a classical

author, Dio Cassius, Roman History 47. 25, 3:

“Brutus stamped upon the coins which were being

minted his own likeness and a cap and two daggers,

indicating by this and by the inscription that he

and Cassius had liberated the fatherland.” The

only securely identified portraits of Brutus occur

on coins inscribed with his name; all others,

whether on coins or other artifacts, are

identified based on the three issues inscribed

BRVTVS IMP (on aurei) or BRVT IMP (on denarii). A

careful study of Brutus’ portraits by S. Nodelman

segregates these inscribed portraits into three

main categories: a ‘baroque’ style portrait on the

aurei of Casca, a ‘neoclassical’ style on the

aurei of Costa, and a ‘realistic’ style on the

‘EID MAR’ denarii, which Nodelman describes as

“the soberest and most precise” of all.

- http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/imp/brutus/RSC_0015.2.jpg

(Hammered down at 120,000DM plus 15% buyers fee.)

Subject: Re: [Moneta-L] Eid Mar (Different Topic)

Date: Sat, 22 Apr 2000 09:54:29 +0100 (BST) From:

"T.V. Buttrey" < t i v b 1

@hermes.cam.ac.uk> To: Grzegorz Kryszczuk <

h i v e 2 @home.com> CC: Moneta-L@egroups.com

Some thoughts. (1) The EID MAR coin is one of the

very few Roman issues actually referred to in an

ancient text, Dio Cassius 47.25.3: "In addition to

these activities [fooling around in northern

Greece in 42 BC] Brutus stamped upon the coins

which were being minted his own likeness and a cap

and two daggers, indicating by this and by the

inscription [EID MAR] that he and Cassius had

liberated the fatherland." [a] Dio wrote in the

late 2nd /early 3rd cent. AD, so obviously used

others as sources. He may be right or wrong, but

he clearly believed that the coin was a symbol of

eleutheria/LIBERTAS, not of suppression of the

Republic. He also gives Brutus and Cassius equal

credit (which Brutus himself didn't always), which

is nicely suggested by the coin: there are several

reverse dies, on all of which the two daggers

differ. [b] Where Dio clearly didn't get the point

is seen in his casual reference to Brutus'

portrait on the coin. Dio was familiar with the

imperial coinages of a couple of centuries; in 42

BC Brutus' coin portrait was astonishing, and

might well have raised questions as to his

intentions, since thitherto [a word I hardly ever

get the opportunity to use] there was only

Caesar's brash innovation, and then the portraits

of the Second Triumvirate guys. However you read

Brutus, this is striking -- even more so on the

aureus where he pairs his portrait with that of

his (putative) ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, the

greatest hero of the Republic. -- Note that

Cassius never portrayed himself on his own

coinage. (2) As to IMP, the title is certainly a

problem with Caesar. In ordinary Republican usage

it ought to mean "acclaimed as victorious

general", and the acclamation, by the troops

and/or the Senate, meant the right to conduct a

Triumphal parade in Rome, the greatest of all

military honors. Caesar had 5 such, and ought to

have labelled himself something like IMPERATOR

QUINTO. But on some of the denarii of 44 BC he is

CAESAR IMP. This has long been worried over. It

can hardly be military in sense. My own guess is

that it has nothing to do specifically with the

military, but reflects his assumption in 44 BC of

the totally unconstitutional title DICTATOR

PERPETUO, and means something like "Permanent

Possessor of the Imperium [i.e. both military and

civil]". You then find Antony as ANTONIUS IMP,

following Caesar's murder, I think necessarily

meaning "I am Caesar's successor as the head of

state" -- not DICTATOR, because that title was by

now discredited. There was certainly no military

victory against non-Romans (those were the rules)

which could have justified Antony's assumption of

the title IMPERATOR. But skip ahead a few years,

and you get his coins with a military trophy and

ANTONIUS IMPERATOR TERTIO -- purely Republican. I

think what happened was that Antony's claim to be

Caesar's successor (and in Caesar's own terms) was

so thoroughly undermined by Octavian, Caesar's

civil heir, and by clever manipulations the

political heir, that he reverted to a

pseudo-Republican stance to set against Octavian's

plainly dynastic direction. This was then spoiled

by his alliance with Cleopatra, but that's another

story. (3) Back to Brutus as IMP. With Caesar as

antecedent you could argue that Brutus was

claiming the same power (and the same as Antony's

claim). But I can't believe that. Insensitive he

was, and not very smart, but to claim the supreme

power -- and that means over all his colleagues in

the tyrannicide, who never gave any indication

that they saw him in these terms -- is so totally

unrealistic: he was, in law, a provincial governor

at the time. Here too we have Dio, in the passage

just preceding the one cited above, 47.25.2: "he

invaded the country of the Bessi, in the hope that

he might at one and the same time punish them for

the mischief they were doing and invest himself

with the title and dignity of IMPERATOR..." Again,

you can accept Dio or not, but he doesn't seem to

be bothered by the title here, and actually gives

it a sensible Republican context (again note the

rules: you couldn't claim the title in civil war,

in fighting fellow-citizens: so you go out and

find some non-Romans to massacre, then claim the

title which was indeed particularly prestigious

[strike fear into the hearts of your enemies,

though they didn't seem much impressed by it: see

Philippi]). To me Brutus' coin, types and title

are no more sinister than that. Ted Buttrey http://www.bitsofhistory.com/moneta-l.html.

- http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/imp/brutus/RSC_0015.3-o.jpg

http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/imp/brutus/RSC_0015.3-r.jpg

Cr-508/3, Syd-1301 (R9), [sothebys.amazon.com

Guarantee] C-15 (350 Fr.); Cahn,

[sothebys.amazon.com] Quaderni ticinesi 1989, no.

10b, pl.II (this coin). Obv: BRVT IMP L PLAET CEST

Head o... read more Minimum Bid: $110,000.00 (No

Reserve) Estimate: (110000 - (In U.S. 150000)

Dollars) Closes In: Closed. Seller: hjbcoins See

more by this seller Number of 0 (starting Bids: bid:

$110,000.00) Description (guaranteed) Ides of March

Denarius, the Nelson Bunker Hunt specimen, 43-42 AD,

Cr-508/3, Syd-1301 (R9), C-15 (350 Fr.); Cahn,

Quaderni ticinesi 1989, no. 10b, pl.II (this coin).

Obv: BRVT IMP L PLAET CEST Head of Brutus r. Rx: EID

MAR Liberty cap and two daggers. Ex Sotheby's, New

York, 19 June 1990, N.B.Hunt, 119; Sternberg, 30

Nov. 1973, 10; Stack's, 20 Nov. 1967, H.P.

McCollough, 1032; and Naville Ars Classica XV, 1930,

Woodward, 1315. Also published in the Hunt

exhibition catqalogue, Wealth of the Ancient World,

no. 119. With this famous reverse type Brutus

commemorates his assassination of Julius Caesar on

the notorious Ides of March, 44 BC, and claims that

the deed was done to secure liberty for the Roman

people (the liberty cap). This sentiment does not

prevent him, however, from placing his own portrait

on the coin, like a Hellenistic monarch and like

Caesar himself shortly before his death! This coin

commemorates the most important single day event in

ancient history. There is barely a person living in

the Western world today who doesn't know the words

written by William Shakespeare, "Et Tu Brute" or the

words Eid Mar inscribed on the rx of this coin. The

fact that a man would commit a political murder and

put the date of that murder and the implements used

to do it on the rx of the coin between which is a

cap representing Liberty and freedom and on the

other side, his portrait and his name with the

inscription IMP or imperator is remarkable. On this

coin, he not only commemorates the act and the day

that he saved the Republic, but contradicts the

meaning and spirit of the rx of the coin by placing

his portrait on the obv and saluting himself as

emperor. Somewhat more than 50 of these remarkable

coins exist. The fact that far more than 50 people

would like to own one, along with the additional

fact that most of these coins are in museums, has

created the justifiable price structure that exists

today. Condition: This coin is nearly EF on the obv,

save a hairline scratch from in back of Brutus' head

to the tip of the T, which I noticed when I viewed

the coin in 1990 at the Hunt Sale. The rx has two

old hairlines above and to the left of the Liberty

cap, but is otherwise EF. With its pedigree, this is

one of the most famous of all the Eid Mar coins.

Additional Specifications Number of Items in Lot: 1

Weight: 3.72g.

Concludo

osservando che la moneta originale, piuttosto rara, è

preziosa perché costituisce un vero e proprio

monumento storico. Quanto alle monete di figura esse

sono invece delle riproduzioni moderne, come si può

rilevare agevolmente dalla piccola "R" sul rovescio,

al di sotto del pileo. Esse fanno parte della serie

dei riconî moderni che negli anni 80 accompagnavano le

confezioni dei biscotti Mister Day - Parmalat.

Concludo ricordando che le monete in esame fanno parte

di una serie emessa negli anni 80 dalla Parmalat come

gadget pubblicitari di una linea di prodotti dolciari

(biscotti/merendine per bambini) denominata Mister Day

(v. link).

Tutte

le

monete

della

serie

recano

una piccola "R" sul rovescio ad indicare che sono

riproduzioni. Un'ultima osservazione è che, essendo le

monete in esame il risultato di una produzione

industriale, presentano caratteristiche fisiche più o

meno identiche (peso, diametro e forma del contorno) e

in ciò si differenziano dalle monete romane autentiche

che, prodotte semiartigianalmente, non garantivano

elevati standard di uniformità. In considerazione

della larga diffusione di queste monete e del loro

contenuto didattico, ritengo utile farne oggetto di

trattazione in questa rubrica.

Cordiali saluti.

Giulio De Florio

--------------------------------------------

>Note:

(1) Denario

(argento). Raccolgo in tabella le caratteristiche

fisiche dei denari di Marco Giunio Bruto tratte

dai link di cui sopra e dal sito

dell'ANS

(American Numismatic Society):

| Riferimenti |

Peso

(g.) |

Diametro

(mm) |

Asse

di conio (h) |

| Link1 |

3,51 |

- |

12 |

| Link3 |

3,72 |

- |

- |

| ANS7 |

3,79 |

19 |

1 |

| ANS10 |

3,72 |

18 |

12 |

La moneta del secondo lettore (3,32g, 19-20 mm)

presenta caratteristiche fisiche sostanzialmente non

dissimili da quelle delle monete autentiche del

periodo.

(2) La moneta fu coniata in

Oriente, dove Marco Giunio Bruto e Caio Cassio

Longino, gli assassini di Cesare, erano andati ad

occupare, per nomina senatoriale, il posto di

governatori, rispettivamente della Macedonia e della

Siria, dopo una fuga precipitosa da Roma determinata

dall'esigenza di sfuggire alla vendetta dei

cesariani. I due si erano ricongiunti a Sardi, città

della Lidia (Turchia) ad Est dell'odierna Smirne e

lì si erano accordati per raccogliere truppe da

opporre, in nome degli ideali repubblicani, ad

Antonio e all'astro nascente della politica romana,

Ottaviano, erede designato di Cesare. Lì avevano

ricevuto dalle truppe l'acclamazione e con

l'approvazione del senato del diritto di fregiarsi

del titolo di "imperator", che veniva concesso ai

generali vittoriosi.

(3) BRVTus IMPerator. Il titolo

di "imperator" concesso a Bruto dopo l'acclamazione

delle truppe è cosa diversa da quello di

"imperatore" oggi utilizzato per indicare gli

"Augusti", i principi cioè o i governanti che si

succedettero nella Roma imperiale da Ottaviano in

poi. In epoca imperiale il titolo di imperator

veniva spesso conferito agli Augusti e aggiunto alla

loro titolatura per evidenziare le capacità militari

del principe. Ciò comporta che quando noi oggi

chiamiamo "imperatore" il principe attribuiamo

impropriamente all'aspetto militare del comando

maggiore importanza che alla funzione civile.

(4) Lucius PLAETorius CESTianus

è il magistrato monetale, al seguito di Bruto,

responsabile della zecca itinerante che batteva le

monete necessarie per pagare le truppe. La moneta in

questione, con lugubre simbolismo, recava sul dritto

l'immagine di Bruto e sul rovescio il

pileo (il berretto simbolo della libertà) posto tra

due daghe, le armi con le quali i congiurati avevano

colpito Cesare nelle Idi di Marzo (15 Marzo) del 44

a.C. Il messaggio della moneta è trasparente: Bruto

rivendicava a sé il regicidio e la libertà

riconquistata con la forza delle armi (Brutus

imperator).

|